Ukraine braces for further cyber-attacks

When the attack came, it took hold quickly and brought a screeching halt to many businesses across Ukraine.

"None of the computers or machines worked except for the General Electric-powered machines like the MRIs [magnetic resonance imaging]," recalled Mykhailo Radutskyi, president of the Boris Clinic - Kiev's largest medical clinic.

His radiologists decided to turn off the body scanners anyway as a precautionary measure after the building's IT system went down at two o'clock in the morning in late June.

Doctors across the centre had to resort to taking records solely by paper and pen for the first time since the mid-1990s.

"The main problem for us was that Ukrainian law requires us to keep all our patient info for 25 years, and we lost that medical documentation for the 24 hours when our systems were down," Mr Radutskyi divulged.

"But thankfully we keep back-ups, so we didn't lose any information."

All in all, Mr Radutskyi reckons his clinic's damage tally totalled $60,000 (£46,000).

Others have been unwilling to reveal how badly they were hit. Oschadbank - one of the country's biggest lenders - was among those that declined an interview with the BBC.

Even now, almost a month after the so-called NotPetya strike, some companies inside and outside the nation are still facing disruption.

Ukraine's top cyber-cop disclosed that some of the nation's largest companies were still too scared to share the full scale of the fallout with his investigators.

And Sergiy Demedyuk - head of Ukraine's ministry of internal affairs' cybercrime division - added he has come to believe there are aftershocks still to come since the hackers appear to have compromised their targets for some time before they pounced, and might still be sitting on data they could yet exploit.

Hijacked software

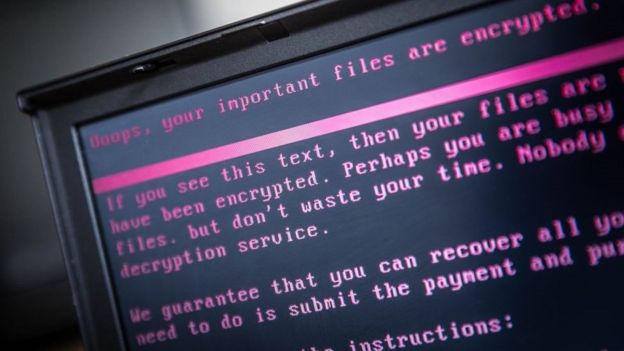

NotPetya initially appeared to be a ransomware attack, but many now suspect its blackmail demands were a cover for something more ominous.

- Hiding out among the net's criminals

- DIY ransomware is "easy to use and free"

- Shoddy data-stripping leads to cyber-leaks

- Pay your fare using a 3D face map

- Cash machine hacked in five minutes

Experts who have spoken to the BBC are seemingly sure of two things: first, Ukraine was the target, and second, it was not about money.

Despite denials, suspicion has fallen on Ukraine's eastern neighbour, Russia.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

"Cyber-attacks are just one part of Russia's wider efforts to destabilise the country," Nato's former chief civil servant Anders Fogh Rasmussen told the BBC.

"In my time as secretary general we agreed that a cyber-attack could trigger Nato's mutual defence clause.

"The Alliance has been assisting Ukraine especially with monitoring and investigating security incidents. However... more support is also needed for prevention."

One cybersecurity veteran has been investigating how a local software developer's program, MeDoc, came to be hijacked to spread the malware.

"It wasn't just [a case of] take over MeDoc's update server and push out NotPetya," explained Nicholas Weaver from University of California, Berkeley.

"Instead, they had previously compromised MeDoc, made it into a remote-control Trojan, and then they were willing to burn this asset to launch this attack," he added, referring to the fact the servers have since been confiscated by the police.

"That really is huge."

MeDoc's tax filing services were used by more than 400,000 customers across Ukraine, representing about 90% of its domestic firms.

Although it was not mandatory for local companies to use it, by virtue of its ubiquity, it's almost as if it were.

"This was gold they had, basically a control point in almost every business that does business in Ukraine," said Mr Weaver.

"And they burned this resource in order to launch this destructive attack."

Comments

Post a Comment